The novelist and philosopher Robert Musil between the great wars stated:

“The remarkable thing about monuments is that one does not notice them.”

It may well have been the case, but more recently they have been anything but unnoticed, and it’s been very rarely to do with artistic value.

Take the one for example, in the Guildhall of William Beckford.

It’s of William Beckford, former Lord Mayor of the City, who famously stood up to King George III (the famous remonstrance as shown in the sculpture) to uphold the rights of free elections and democratic principles for his scoundrel friend and libertine John Wilkes in 1770.

He is an integral part of the curriculum for any City Guide doing the Guildhall exam, and it is the earliest sculpture in the hall.

However we also learn about his darker past – that of an unrepentant slave owner, enriched by over 3000 slaves in Jamaica to be one of the richest people in the country, and, according to his biography by Perry Gauci, approached by anti-slavery campaigners and refused to even reply to them.

In fact, the book reveals, he even named a pair his slaves without any irony “Wilkes” and “Liberty”.

In recent months, following the Black Lives Matter movement, the toppling of the slaver Colston’s statue in Bristol, the removal of the slaver Robert Milligan from the Museum of Docklands entrance and the renaming of the Sir John Cass primary school to the Aldgate school, the Corporation of London commissioned a public consultation about the future of the Beckford statue.

The latest news on this is that although the Corporation decided to resite the statue following the consultation, Robert Jenrick the Communities Secretary has written to the Corporation in February asking them in the strongest terms to “reconsider”.

My own opinion is that is a proper responsibility of community representatives to review their public monuments, which are by their nature public statements.

This includes the right to remove or resite them, as long as they have properly consulted with the communities they represent, and I fully support the actions of the Corporation in this case, both in the effort to consult and secondly in the decision.

I would also go further and put up some form of monument in George Yard between Cornhill and Lombard Street to the campaign for the abolition of slavery, but that is for another post.

There is an interesting precedent here, showing that it is firstly not a new topic and secondly not reserved to supposed “woke” activists.

I refer to that bastion of radicalism, the Daily Express.

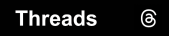

In November 1998 their headline was below:

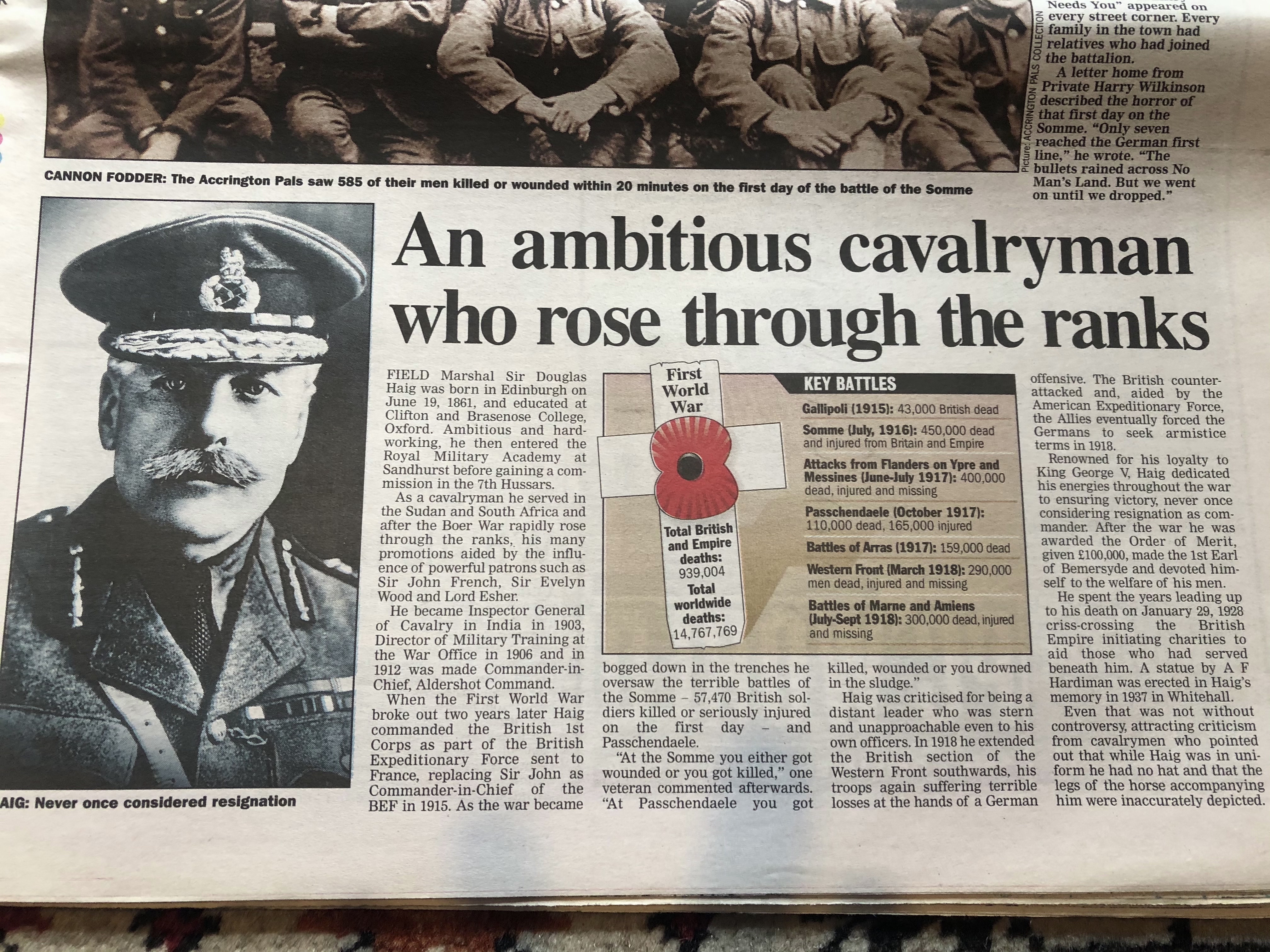

The paper went on to demand that the statue of General Haig, commander of the British Expeditionary Force in World War 1 including at the Somme, be removed. It is in Whitehall, just north of the Cenotaph and facing it, and has been an incredibly controversial memorial even in its own time.

The paper then enumerates the case against Haig.

It had been proposed by the Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin after Haig’s death in London in 1928, and even leaving to one side Haig’s war record as discussed in the Express above (which has more recently been subject to less damning research by academics such as Gary Sheffield), as a work of art it was controversial. I was first made aware of it reading Anthony Powell’s “A Dance to the Music of Time” where the anti hero Widmerpool says”

“The question, to my mind,’ said Widmerpool, ‘is whether a statue is, in reality, an appropriate form of recognition for public service in modern times.”

The memorial was bitterly criticised by Haig’s widow and had to be remodelled. The sculptor Alfred Hardiman went bankrupt, the changes forced pleased no-one, and it ended up as neither a classical nor a modern naturalist creation, especially the horse, in fact it was the last real attempt to portray a military leader in an equestrian pose, an anachronism in an age of tanks, barbed wire and gas.

I talk about statues and evaluating the past a lot more on my walks, please come, but I’ll just say now two things:

Firstly, it is a responsibility to regularly evaluate the past. No doubt future generations will come to their own opinions on the beliefs and decisions of our time, and may well bitterly regret and criticise them.

Secondly, this is not a reserve of “woke” or radical politics, but cuts across all political and social spectra.